The Central Melbourne is a rectangular city area, in the shape of grids in planning. However, the events and activities happening on the streets here are so rich and diversified that people are unaware of its compact spatial scale and the regular and precise original planning of the city space. From the perspective of urban space,Melbourne is totally different from those metropolises beginning to develop after the Renaissance of Europe, where there are vast and geometrical city areas, spectacular boulevards, and splendid city squares. By contrast,Melbourne is not big in size, whose streets and roads are not magnificent, or even a little narrow, without many admirable city squares. Melbourne is also not the same with those European old cities which naturally grew after the Middle Ages with complicated and varied arrangements. Instead, its downtown is planned to be fairly neat and tidy rectangular grids. At the first sight,Melbourne seems to be a clear-cut and boring city, a destination where a tourist would never lose the way, and a place where there is no unexpected surprise at all.

However, when you really go into it, you would find that the public life of Melbourne is so rich in urban treasures which are waiting for you to discover. The brilliance of Melbourne’s public life has nothing to do with the size of the space, or the magnificence of the architecture. Everything is natural, casual, but mysterious. Here in Melbourne, the various small streets and alleys are undoubtedly the most interesting and most attractive city space. Open an official tourist guidebook randomly, and you will find a lot of suggestions on visiting the small streets and alleys in the centre of the city, such as the Hardware Lane which is described as “the most beautiful and cheerful lunch place in Melbourne”, and the fascinating bar hiding near Little Collins Street. Stroll in the Little Collins Street, occasionally turn to the narrow space between two buildings, and you will find so many people sitting in the lane, smiling and drinking coffee. It feels like that you have arrived at the magical heaven after crossing a mysterious area. In this urban space, which is narrow, hidden and even a little bit dark, the city life appears highly vivid, while the power and charm of Melbourne blossom in this tiniest space of the city. At this point, the names of the streets and the alleys don't matter any more, for they have become a natural state of residents and visitors to participate in and experience the urban civil life. Here, the “small” urban space doesn't hinder the existence and growth of civil space at all. It is just this capillary-like small space that breeds the “big” civil space everywhere.

In the centre of Melbourne, the small streets and alleys and the relevant culture, represented by Block Place, Centre Place, Hardware lane, and Degraves street, have become an importance feature and attraction of the city, significantly influencing the varieties of new architecture design in current Melbourne, such as Queen Victoria Village, Urban Workshop at 50 Lonsdale Street, 550 Bourke Street, and other complex buildings. This paper intends to explore Melbourne’s various attractive and widely praised aspects of its street-and-alley urban space by analysing the spatial features and urban relations of traditional streets and alleys, in order to reveal how the small street space of Melbourne facilitates the richness and expansion of civil space broadly and positively.

Historical Development of Melbourne’s Small Streets and Alleys

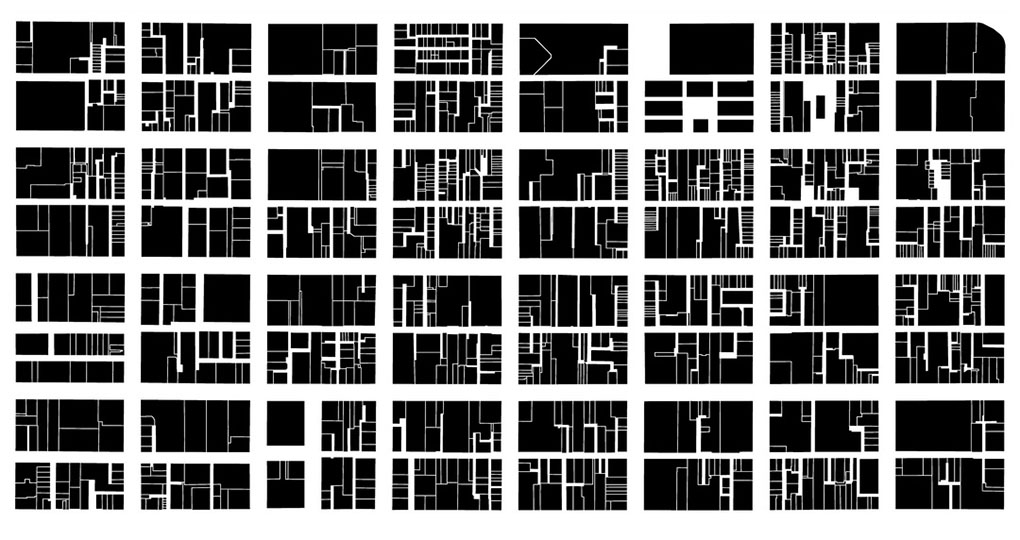

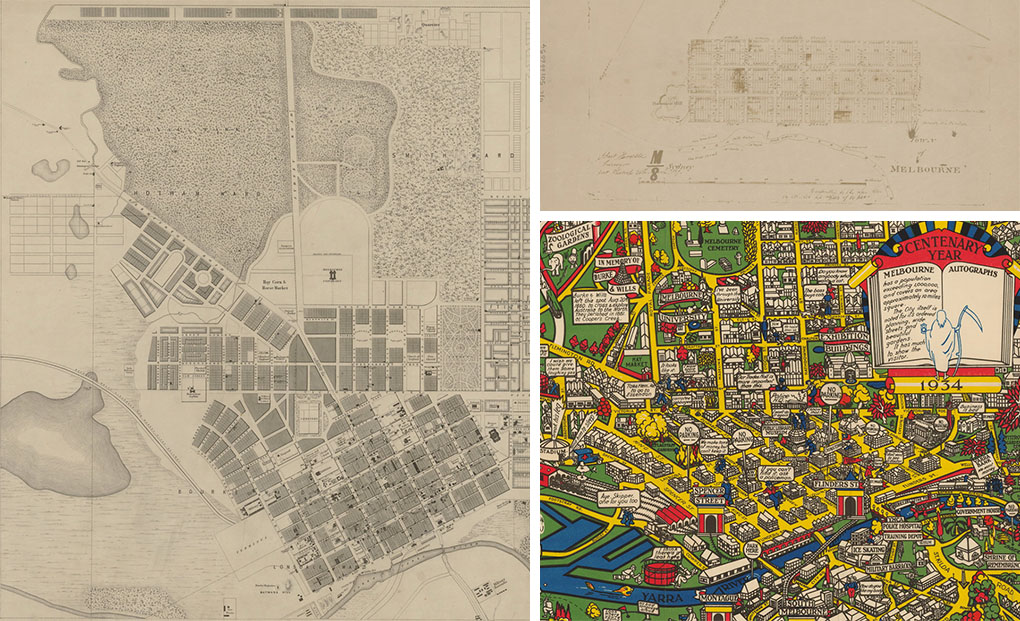

Before discussing the charming street space of central Melbourne, it is necessary to get a basic understanding of the city’s space development. The original planning of the urban area began with the street layout designed by Robert Hoddle in 1837, called “Hoddle Grids”. This grid layout is the well-known current central urban area of Melbourne. According to Girds & Greenery published by Melbourne City Design and Construction Bureau in 1987, the this kind of small streets and alleys in the big city blocks was designed to guarantee the efficient use of the blocks, serving as logistical lanes to keep the main streets clean and tidy, and the width of these alleys normally only met the necessary demands of cars and passengers at most.

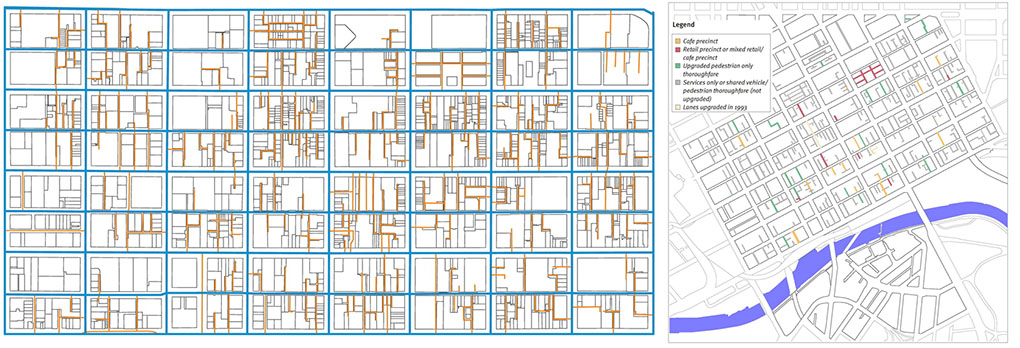

In the nineteenth century, the urban area was further divided in order to adapt to the development of the city with increasing density. This change urged the complicated streets and shopping arcades to develop in a lot of big city blocks, and at the same time many streets and alleys began to turn into walking shortcuts that citizens preferred to use, increasing the shopping space of the city. The central Melbourne gradually formed the double street space system: one was the open and tidy main street network, and the other was the varied small streets and alleys as well as city arcades[1]. In the downtown, there were only a few city squares which were limited in spatial scale, thus this closely related, extensive and just-the-right-size street system constituted the major urban public space of Melbourne. The updating and activating strategies for the downtown after 1980s also gave richer city public vitality to the street space.

Public Space and Public Life

As Melbourne’s main city space, these small streets and alleys are broad civil space full of public vitality. The key is that they can meet the needs of public social life. As the famous German sociologist Georg Simmel once said, we need to be part of others, close social circle, family, community, country and even the human being[2]. As socialized animals, people observe, listen to, touch, talk to, discuss and participate in social life directly in public space and the traditional streets make up most of the city public space[3]. Since the origin of the first human settlement, streets have become the key places for civic engagement, information communication and exchange of ideas[4]. However, modern city streets have lost this initial social function. The spatial scale and function design of streets can not satisfy the public social demands, and many streets tend to develop into single-function urban traffic systems, ignoring their innate mission as public space. The communication between social members gradually dilutes during the changing process, leading to the lack of real public space in the city[5]. In view of this phenomenon, Alexander points out clearly that nowadays the problem of city streets is actually the problem of promoting civic engagement[6]. Different from those streets based on the sole function of modernistic thoughts, the small streets and alleys in Melbourne support and facilitate the communication, participation, interaction and city life in the urban space with their locations in the city planning structure and their spatial characteristics.

The Contribution of Streets and Alleys to Accessibility and Permeabilty

First of all, these streets and alleys are highly accessible. Just as the famous urban theorist Jane Jacobs says, the primary purpose of streets is for people to go from one place to another, and make connections with surrounding areas surpassing the streets themselves. A good street must be easy to find, well connecting the surrounding area and the public space system of the whole city. Let’s take the example of Block Place and Centre Place which play the important roles of connecting different city functions, different city blocks and neighbouring main roads.Block Placeis the shortcut from Collins Street to Little Collins Street, connecting the neighbouring city blocks and the internal functions of the streets. These streets and alleys are part of the urban pedestrian traffic system, instead of existing as isolated paths. Viewing from the perspective of the scale of pedestrian activities in the central area,Block Place and Centre Place are integrated with other streets and city arcades, providing a direct and convenient pedestrian path from Flinders St. Station, the central train station in the south margin of the downtown, to the centre of the city. On the other hand, in smaller urban areas, the streets and alleys serve as distributors for people to reach city blocks to participate in activities with different functions. Their spatial features enable massive people to use them pleasantly, and the intensive public activities trigger abundant small business activities on both sides of the street space. In the study of social behaviour, more public activities mean more opportunities to observe, listen to, touch, talk to, discuss and participate in social life, which can trigger other related public activities, forming a virtuous cycle and self-reinforcement. It is thus clear that the highly accessible small streets and alleys not only work as the connections of different functions and distributor of people flow, but also provide fertile soil to breed social public activities and communication.

Diversity and Richness Generated by Street Space

Another factor that urges the small streets and alleys to become the most important urban public space in Melbourne is the diversified use and the users. As Jane Jacobs states, a complex street space mixing different purposes makes the city safer, more liveable and more attractive. She also placed great emphasis on the four aspects of the diversified space use to improve the quality of the streets: to maintain the consistency of the urban activities in most of the day and the night; to increase safety of the streets through the existence of road users; to decrease the monotony of the city space; to increase the mutual contact of people in public space and the combining use of city functions[7]. In central Melbourne, the diversified use functions of the small streets and alleys provide the public and users with not only different experiences, but also opportunities for self-definition. They also create a lot of mutual communication among people with different backgrounds. Entering the streets and alleys, people can see the signs showing the names and functions of the shops inside. For example, Block Place also combines many other functions such as bookstores, CD shops, optical stores, beauty shops, hair salons, basement discos, boutiques and jewellery stores, though it is dominated by restaurants and cafes. Meanwhile, the users here are of different cultural backgrounds, ethnic groups, and ages. Most of the day, the streets and the alleys are always crowded, and the cafes along the sidewalks are full of customers. It has become a way of participating in the social public life to sit here and observe the passersby, or in other words, to enjoy the existence of others. When users with different backgrounds coexist in the same space, the simple activities happening here, such as walking, observing, meeting and eating, begin to correlate with and influence each other. These simple activities endow the streets with diversified public life, which further enhances the public communication and interactive place effect.

At the same time, in the small streets and alleys represented by Block Place and Centre Place, most shops and stores cover only a small street frontage, which can shorten the distance between the exits and entrances of different functions, while most communication and interaction happen near the entrances. According to the research of Jan Gehl, compared with small and active street frontages along the streets, the big units by the roads would clearly decrease the street life[8]. Smaller street frontages imply more multiplicity, which can hold more functions and stores. Jane Jacobs suggests that the city space should be diversified, and the diversification of the small streets and alleys in Melbourne is embodied in the different show windows and scenery, changes in the colors, and the subtle transformation of buildings as time goes by. The variation and diversity are likely to happen gradually, instead of a one-time sudden change. The progressive growth of architecture adds the visual effect of the urban space and creates a feeling of continuity. Their traits bring closer communication, touch and interaction to public space, which happen not only between different people, but also in the collision of people, buildings, advertisements, commodities, decorations and colors.

Human Scale contribute to Public Life

The small scale of these streets and alleys is helpful to make them appropriate places for communication and social contact. They are normally from three meters to seven meters wide. The two typical streets,Block Place and Centre Place, are three meters and four meters wide respectively. Some theorists believe that small space let people see and hear others’ behaviours and perceive details of the small space. Edward T. Hall, an anthropologist and cross-cultural scholar, defined some social behaviour distances, including intimate distance, personal distance, social distance and public distance[9]. The social distance is about from 1.30 meters to 3.75 meters long, which is usually the distance when talking to friends, acquaintances, neighbours and colleagues. The public distance is more than 3.75 meters long, in which people can see or hear others without involvement. Considering that part of the streets and alleys have been occupied by chairs along the road, the actual accessible width of the streets and alleys is about two or three meters. This precisely conforms to Edward T. Hall’s definition of social distance. Therefore, if you want more privacy, this spatial scale may result in the feeling of congestion. However, if you would like to participate in public life and communicate with others, the physical scale of the street space can exactly encourage such activities.

Comfortable and Safe Spatial Features

What is more, the comfort and safety the street space offers are also significant reasons why it can breed rich public life. Though subject perception, comfort and safety are still influenced by many physical factors. Allan B. Jacobs comments like this: the best street is comfortable, at least in its possible range. when it’s cold, it can give people warm sunshine; when it’s hot, it can offer shelter from the heat … The nice city streets can always offer people shelter from wind and rain. He also took the example of the streets in Rome and Copenhagen to point out that it is the narrow streets and the natural continuation of the buildings on both sides that create such comfort[10]. The small streets and alleys in the centre of Melbourne have these space characteristics as well. They are all relatively narrow facing the south and the north, which can protect them from the strong wind and make sure that the sunshine can reach the ground even in cold days. Small space can also make people feel warmer with more feelings of personal space.

The security sense of urban public space can be divided into two parts: avoiding the interference of automobile transportation and getting away from crimes[11]. Urban public space, especially the streets, is normally divided into driving area and walking area by kerbs or sidewalks, but this physical division can not necessarily eliminate the insecurity brought about by automobile interference. However, you never have to worry about this walking on the small streets and alleys in the centre of Melbourne, because most of them are walking systems without car interference at all. Likewise, people won’t have any feelings of insecurity about the public order. Jane Jacobs holds that the streets are the safest when people are willing to use the streets and enjoy the street life. She also emphasizes that the premise of such safety is the support mechanism of social security by means of spontaneous, virtuous, and natural surveillance of people who use the abundant shops and other public places on the sides of the sidewalks in every period of time during the day[12]. Most cafes and shops on the streets and alleys in Melbourne open all day long, and more importantly, the diversified shops and street functions attract different people to use the streets, which can retain the high use density all the day, finally forming the “eyes-on-the-street” support mechanism of public security suggested by Jane Jacobs.

In addition to the integral readability, accessibility and relatively clear spatial structure, these small streets and alleys also contain unexpected surprises. Though a little narrow and even a bit dark, the urban space is comfortable, safe and public. That’s why they are breathtakingly mysterious, waiting for people to discover and experience. Such multiple collision of unexpected public life further enhances the impression of the urban space as public places on visitors.

The Influence of Traditional Street Space On Recent City Design of Melbourne

Compared with the early new buildings in the city centre such as Melbourne Central, the diversity and publicity embodied by the street space and street culture in central Melbourne, represented by Block Place and Centre Place, largely promote and activate the economy, culture and life of the city, which undoubtedly explains the street tendency of recent city design and architecture design in Melbourne. When examining the city arrangements of the downtown, you’ll find that the traditional city arrangements have been replaced by continuous city architecture in the centre of Melbourne. The aisle space inside the shopping malls have taken place of the traditional streets. In light of this change, many architecture theorists stress that the public space in privately controlled buildings will cause spontaneous public life to fade away, resulting in the hollowing out of various activities and colorful attraction in public space. Meanwhile, some contemporary architecture forms, such as the ordinary shopping centers in the downtown of Melbourne, can not really meet people’s social requirements. As sociologist Mark Gottdiener points out, people try to look for social public life in privately controlled shopping centers, but they won’t be satisfied[13]. The instrumentalized city architectural space has removed the public social life and its essence --- spontaneity and freedom. Compared with the contemporary architecture type, the traditional street space of Melbourne has obvious advantages to shape the urban public life. This also explains why traditional street space was introduced to several new city designs again after 1980s under the guidance of the activation strategy in the downtown of Melbourne, which is more and more widely influencing new architectural design afterwards. Such new streets and alleys as Shilling Lane, Albert Coates Lane and Red Cape Lane at Queen Victoria Village,Madame Brussels Lane at Urban Workshop, and Golds brough Lane at 550 Bourke Street are the latest interpretations of Melbourne’s traditional street space. These new buildings continue and duplicate the arrangements of the small streets and alleys which are the most unique feature of Melbourne, and try to introduce this type of activated public life and space in new city blocks.

The activation of downtown urban public space in Melbourne, particularly the small streets and alleys, gives rise to the current broad and rich city public life and civil space, making immeasurable contribution to the diversified central areas and dynamic city characteristics. With further development and increase of downtown urban life, it can be predicted that more inactive streets will develop into new vessels for Melbourne’s urban public life. The traditional old streets and alleys and the modern ones in new buildings together make up the spatial arrangements with unique features in Melbourne. Though small in size, they contain the richest and the most prevalent public life and civil space, where the city life is full of surprise and distinct glamour, forming Melbourne’s unique character and city experience totally different from those of other cities. It can be said that the “big” urban public life of Melbourne is based on its “small” city space. This seemingly contradictory cause-and-effect relationship tells exactly the essence and core of urban public life.

[1] Grids & Greenery: The Character of InnerMelbourne, 1987, Urban Design & Architecture Division, Melbourne, p 56.

[2] I Altman, The Environment and Social Behavior, Brooks/Cole Publishing Company,Monterey1975, p 49.

[3] J Gehl, Life between buildings, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc.,New York1987, p 15.

[4] T V Czarnowski, ‘The Street as a Communications Artifact’, in On Streets, ed. S. Anderson, the MIT press, Cambridge 1978, p 207.

[5] Ibid.

[6] R Gutman, ‘The Street Generation’, in On Streets, ed. S. Anderson, the MIT press,Cambridge1978, p 261.

[7] G Levitas, ‘Anthropology and Sociology of Streets’, in On Streets, ed. S. Anderson, the MIT press,Cambridge1978, p 235.

[8] J Gehl, Life between buildings, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc.,New York1987, p 97.

[9] Ibid, p 71.

[10] A B Jacobs, Great Streets, the MIT press,London1993, p 275.

[11] A Rapoport, ‘Pedestrian Streets Use: Culture and Perception’, in Public Streets For Public Use, ed. A. V. Moudon, Columbia University Press, New York 1991, p81.

[12] J Jacobs, ‘The Use of Sidewalks: Safety’, in The City Reader, ed. T. L. Richard & F. Stout, Routledge,London1996, p 106.

[13] M Gottdiener, ‘Recapturing the Center: A Semiotic Analysis of Shopping Malls’, in Designing Cities: Critical Readings in Urban Design, ed. A. Cuthbert, Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p 135.